Dynamic Duo

Lily, one of Brookfield Zoo’s grey seals, greets Dr. Jennifer Langan (left), senior staff veterinarian, Chicago Zoological

Society, and clinical professor of zoological medicine at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine; and

Dr. Michael Adkesson, vice president of clinical medicine for the Chicago Zoological Society, which manages the zoo. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

Lily, one of Brookfield Zoo’s grey seals, greets Dr. Jennifer Langan (left), senior staff veterinarian, Chicago Zoological

Society, and clinical professor of zoological medicine at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine; and

Dr. Michael Adkesson, vice president of clinical medicine for the Chicago Zoological Society, which manages the zoo. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society) The dolphin looks to be in heaven. Her chin is tilted out of the water; she’s gripping the wall with her flippers. She gulps a piece of fish and opens her mouth for more. The trainer tosses ice cubes and the dolphin lets loose a series of delighted clicks.

“Dolphins get excited to interact,” says Dr. Jennifer Langan, ’94 VM, DVM ’96, senior staff veterinarian, Chicago Zoological Society and clinical professor of zoological medicine at the UI College of Veterinary Medicine. “They’re very engaged. They enjoy attention. It’s like a guest is ringing their doorbell.”

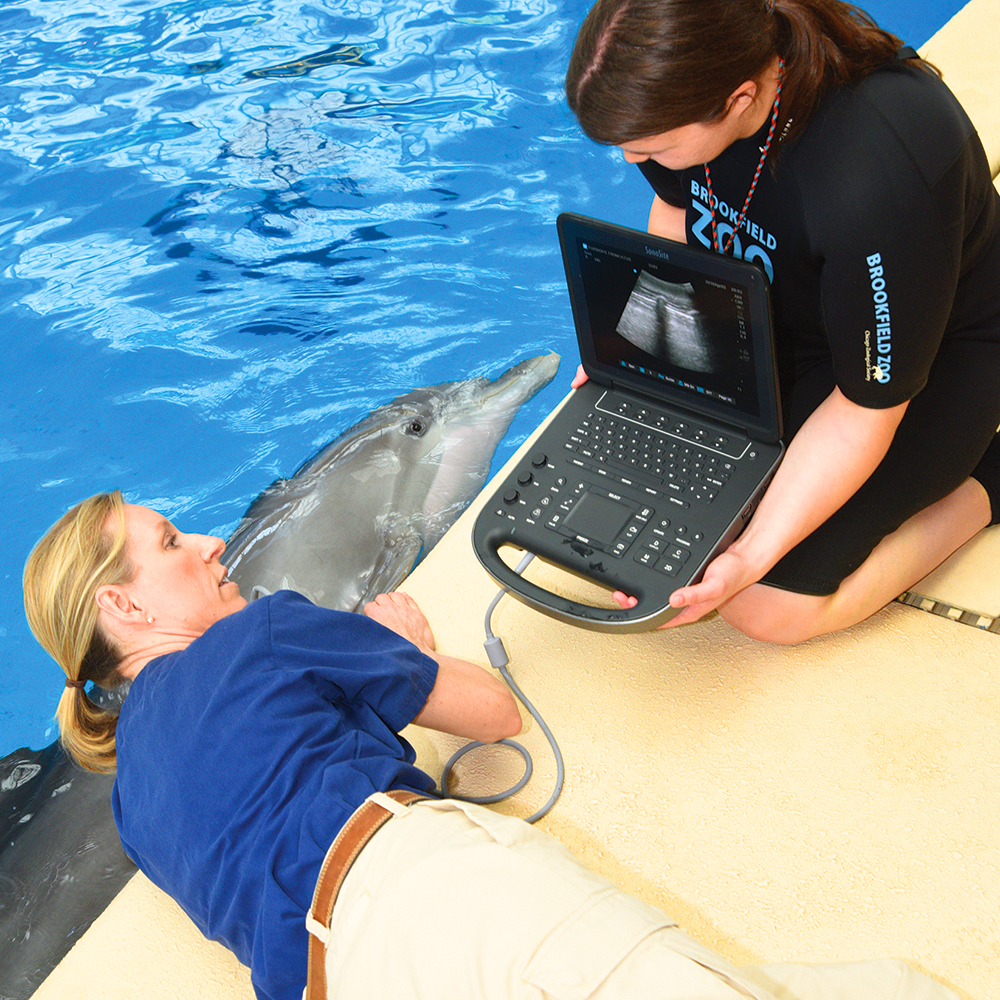

Langan is at the Brookfield Zoo’s dolphin habitat this morning to perform an ultrasound on her patient, Spree. She leans over the water and takes a friendly but firm grip on Spree’s fin.

“You can’t ever forget they’re wild animals,” Langan says. “You have to treat her with respect.”

Langan conducts an ultrasound on Spree, a bottlenose dolphin. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

The two mammals seem to understand each other. At a nudge from Langan, Spree rolls onto her back so that Langan can run her scanner over Spree’s left lung while she checks the monitor. Langan moves the scanner to look at an ovary. With the help of an animal care specialist, she rolls Spree onto her other side to check her right lung, noting, “What a cooperative patient!”

Langan gives Spree a parting rub on her tummy. If it’s not obvious, she loves her job taking care of the more than 3,000 animals at Brookfield (Ill.) Zoo.

“It’s never the same thing twice,” Langan says. “One day it’s a tiger with a toothache or a wolf with a limp. Then it’s a bird that’s not interacting with other birds or a monkey that’s sneezing.”

Next up this morning is Hani, a sloth bear, who is having her annual check-up at the Zoo’s animal hospital. Unlike dolphins that need to stay amused to be good patients, Hani is out like a light. When Langan joins 10 other zoo staffers gathered around the examination table, Hani has already been under anesthesia for an hour. A veterinary technician finishes up her dental exam and polishes the bear’s teeth, while a veterinary resident completes her ultrasound examination. Then it’s time to roll the furry 300-pounder onto a stretcher and wheel her down the hall for a CT scan. Overseeing all these procedures is another Illini, Dr. Michael Adkesson, DVM ’04, vice president of clinical medicine for the Chicago Zoological Society, which manages Brookfield Zoo. He oversees a staff of 20 and all activities at the zoo’s hospital.

“An ultrasound on a sloth bear can be difficult because of its size and fur. We try not to shave the entire belly, which you might do for a dog or cat,” Adkesson explains. “For the bigger carnivores, we do preventive care exams every two or three years. Anesthesia has an impact, just like with humans. It’s a balance of the health information gained and the after-effects of anesthesia.”

Adkesson hovers over the monitors that show Hani up on the table being positioned under the doughnut-shaped scanner, the largest CT machine on the market. “We need to make sure she’s straight, so the images are straight up and down, like a loaf of bread. We need to make sure we’ve got the right energy to penetrate her width,” he says. As for the CT machine, “We can scan just about any animal at the zoo—polar bears, zebras, tigers. You just have to fold their legs properly,” he adds.

Folding the animal’s legs wasn’t a solution last year when Layla, the rhinoceros, developed an impacted tooth, which led to secondary issues that blocked her airway. The 2,300-pound rhino is only one of two animals—the other being a giraffe—that won’t fit through the hospital’s big double doors or into the scanner. But something had to be done.

(Left) Adkesson (far right) directs his team on positioning Layla, a 2,300-pound eastern black rhinoceros, onto a mat in preparation for her CT scan. A portable CT unit was used because she is too large to move inside the zoo’s animal hospital. (Images courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

“It was very difficult for us to visualize what the problem was without a CT scan,” Adkesson says. “We needed to get in there to understand it and then target the surgical approach.”

Thanks to Adkesson’s efforts and the Zoo’s clout, the hospital was able to borrow a portable unit from Samsung-Neurologica, a scanner manufacturer. Then it took 40 Chicago Zoological Society employees to hoist the anesthetized rhino onto a specially built platform and transport her to a location where vets could use the scanner. Layla was the first living adult rhino to undergo a CT scan. After several subsequent surgeries, veterinarians are optimistic about her prognosis.

“Ten years ago, Layla probably would not be with us,” Adkesson says. “Now, we hope to get her back to a long, healthy life.”

Adkesson is extremely proud to be working at a zoo that helped pioneer the use of advanced technology. Brookfield Zoo got its first scanner in 2010 and upgraded to a newer machine in 2016. It remains one of only six zoos to own one. Not only do CT scans provide high-

resolution views, but they enable those digital images to be sent around the world for instant comparisons. When Kasha, an Amur leopard, was anesthetized to resolve dental problems, Adkesson and the zoo’s veterinary radiologist—Brookfield is the only zoo to have one on staff—obtained scans to add her dental images to a growing database of scans from healthy animals that can aid diagnostic evaluations.

The scanner has been used on turtles and armadillos because X-rays can’t easily penetrate the animals’ protective armor. It was used on a pangolin—also known as a scaly anteater, native to a few places like Togo—to evaluate its astonishingly long tongue. The animal’s tongue base wraps around its right kidney, and previously, its anatomy had never been fully described. In addition to facilitating the pangolin’s future care, Adkesson hopes that knowledge about this unusual feature will galvanize interest in the pangolin, the world’s most trafficked mammal, whose scales are prized in Chinese medicine.

Adkesson examines a young, white-bellied pangolin, an endangered species because of poaching and wildlife trafficking. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

“Our hope is that our managed population will serve as ambassadors for their counterparts in the wild,” Adkesson says. “We have more than 2 million visitors come through the zoo every year, and this is an opportunity for them to engage in a conservation story about this animal and become passionate about its survival.”

Ambassadors for conservation

Conservation is a major priority at Brookfield Zoo and of particular interest to both Langan and Adkesson. A native of Decatur, Ill., Adkesson has been excited about zoos and conservation since he was a boy. He found that veterinary medicine provided a path to explore those dual passions during his residency training at the St. Louis Zoo. That was when he developed a two-week research project to study penguins on a rocky stretch of the Peruvian coast. The site, Punta San Juan, is home to as many as 6,000 of Peru’s 15,000 endangered Humboldt penguins. The reserve and its connected beaches are also the residence of as many as 5,000 fur seals, 12,000 sea lions and 500,000 cormorants, terns, boobies and pelicans.

Adkesson and Langan examine a Humboldt penguin at the Punta San Juan reserve in Peru in 2008. A decade later, the Chicago Zoological Society’s veterinary staff continues its health assessments on the region’s wild Humboldt penguins and marine mammals. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

Since his first trip to this astonishing preserve in 2007, Adkesson has visited Peru more than 20 times. The Chicago Zoological Society and its partners have sent research teams, and are committed to turning Punta San Juan into a hub for the global study of marine wildlife. The Zoo also has supported conservation efforts by serving as a kind of laboratory to facilitate the use of tracking data to monitor animals. For instance, it is difficult to tag animals such as seals and sea lions, Adkesson explains, because anesthetizing them in the wild carries serious risks. Living on beaches, they are always in danger of wandering into the water and then falling asleep and drowning.

“The knowledge we’ve gained in a zoo setting, working with different anesthetic drug combinations and monitoring methods, is invaluable,” Adkesson says. “It helps us put satellite tags [on wildlife] to monitor their movements and evaluate their health and genetic diversity. It also helps us determine the food they eat and where they’re foraging.”

Like Adkesson, Langan was drawn to veterinary medicine because of a long-standing interest and passion to contribute to global conservation. “Growing up, I loved spending time in our national parks, working with injured wildlife and caring for our family pets,” Langan says. As an undergraduate at Illinois, she focused on animal science and theriogenology (the study of animal reproductive systems) because of her interest in saving endangered species from extinction. As a graduate student in the UI veterinary program, she learned how a career in zoological medicine “would allow me to do what I loved as well as provide me with the opportunity to teach bright minds who wanted to pursue a similar career path,” she says.

A general practice veterinarian can start caring for small domestic animals such as dogs and cats immediately after earning a DVM degree. But zoo veterinarians, like others who specialize in veterinary cardiology or anesthesiology, must complete a one-to two-year internship and a three-year residency. Langan, who completed her internship in Boston and her residency at the University of Tennessee, was the first veterinarian in Illinois to be board-certified by the American College of Zoological Medicine and for quite some time was the only state vet with that qualification.

Langan (center) listens to the heart and examines the ear of Zenda, a male African lion, during a preventive health-care examination in the zoo’s animal hospital. (Image courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

Langan started at Brookfield Zoo in 1999, and it didn’t take long before her training and improvisational sangfroid were put to the test. On a busy summer morning, she arrived at the zoo to find that, overnight, Aussie the polar bear had suffered an acute abdominal hernia.

“There were very few staff that morning and thousands of park guests, and I had to figure out how to arrange emergency surgery on a 1,000-pound polar bear,” Langan recalls.

Within hours, she had mobilized zoo carpenters to build a special surgical table to accommodate Aussie, who is more than 11 feet long, and arranged for a bulldozer and a forklift to move the bear across the park, accompanied by a police escort to help navigate the crowds. Langan found a large-animal surgeon at the UI College of Veterinary Medicine who agreed to drive up from Champaign and repair the hernia. Most importantly, she took extra care to ensure that Aussie was asleep when they opened the door to his enclosure.

“Polar bears are incredibly smart animals, and on several occasions, have played like they were asleep,” Langan says. “It was very tense and exciting, and there were lots of safety concerns and logistics. Fortunately, everything went as planned and three weeks later, Aussie was back to swimming again.”

In addition to her work at Brookfield, Langan is a clinical professor at the Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine—the school’s first faculty member to reside at Brookfield Zoo—and runs UI’s residency program there (see sidebar). It’s an aspect of her work that she particularly enjoys.

“It’s like a specialty referral and teaching hospital,” Langan says, “with the vets and vet residents working side-by-side. What makes zoological medicine such a fantastically interesting field is that there is so much that is unknown and so much we have to learn. What might surprise people most is how much research we do and the level of cutting-edge medicine we practice.”

A small sample of their efforts are up on the bulletin board in a zoo conference room, where photocopies of recent papers are posted. Alone and together, Langan and Adkesson have authored more than 75 articles. Most are aimed at colleagues or other professionals. Papers with titles such as “Pharmacokinetics of the Long-acting Intramuscular Antibiotic, Excede, in Helmeted Guineafowl” or “Osteochondral Autograft Transfer for Treatment of Stifle Osteochondritis Dissecans in Two Related Snow Leopards (Panthera uncia)” are not likely to grab attention from casual zoo fans, but they do suggest such research can further both veterinary procedures and the safe study of animals in the wild.

The more data that zoos like Brookfield can gather on species whose survival is at risk, the more effectively they can lobby for conservation.

Adkesson performs an ultrasound on a polar bear. Langan checks a tiger’s eye. ((Images courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society)

“If we understand an animal’s basic physiology, how often they reproduce, how much space they need or the types of food in their diets, we can make strong recommendations based on science,” Adkesson says. “Without those targeted objective points, it’s very hard to get government buy-in to protect a species or park.”

Back at the dolphin pool, Langan is finishing up her ultrasound notes while Rita Stacey, Brookfield’s marine mammals curator, explains why Langan is such a terrific vet.

“I remember when Dr. Langan first started and I saw her in action,” Stacey recalls. “She’s so personable. She’s got what we like to call great ‘dockside manner,’ which is so important in understanding dolphin behavior.”

Langan packs up her monitor and comes over with a smile. The news is all good. The tiny cyst on Spree’s ovary has resolved. There’s a small scratch on her right side, nothing serious; they’ll keep close tabs on it. Her lungs look clear.

“Now we have to get to the sloth bear,” she says, “and then the giraffe!”

Dr. Karen Terio, head of the UI College of Veterinary Medicine’s Zoological Pathology Program, studies chimpanzee health in Tanzania. (Image courtesy of Karen Terio)

Diagnostic Services

How the Zoological Pathology Program’s work benefits animals

The UI College of Veterinary Medicine’s Zoological Pathology Program, a section within the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, provides diagnostic services to a host of global organizations, including wildlife agencies, conservation groups and zoological facilities. The study of pathology has provided a vital key to improving the lives of wild animals. Despite leaps in technology, it can be difficult to ascertain what, if anything, is bothering an animal or contributing to its poor health. Animals have evolved to mask signs of weakness, such as an arthritic knee. “The animal that limps on the savanna,” Adkesson says, “is the first one to get picked off.” Post mortems on animals—“necropsies”—often offer the best clues into disease progression, offering a great value to zoo vets who would like to see their charges live into what Adkesson calls their “golden years.”

The UI pathology faculty is known for its expertise and broad-ranging commitments. Dr. Karen Terio, clinical professor, who heads the program, is senior editor of the recently published Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals, considered the definitive textbook on the subject. Dr. Kathleen Colegrove-Calvey, clinical associate professor, led an important research study of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill into the Gulf of Mexico and its impact on generations of dolphins. This past May, Colegrove-Calvey was named president of the International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine at the organization’s 50th annual meeting in Durban, South Africa. Dr. Michael Kinsel, ’91 VM, DVM ’93, clinical professor, who previously headed the program, is a globally sought-after expert for his experience with marine mammals, wildlife and zoo animals. Dr. Jaime Landolfi, clinical assistant professor, is well-known for her groundbreaking research into the immune response of elephants afflicted with tuberculosis. Dr. Martha Delaney, clinical assistant professor, is the newest addition to the fulltime faculty, and studies innate immunology of various zoo, aquatic and wildlife species.

Collectively, ZPP has contributed hundreds of articles to scientific publications and developed a full-service pathology laboratory where samples from around the world are sent for disease

diagnosis and outbreak investigation.—J.B.

Dr. Lauren Kane, a zoological and aquatic animal resident, examines a black bear as the College of Veterinary Medicine team performs animal checks at Wildlife Prairie Park, a refuge featuring native Illinois animals. (Image courtesy of Fred Zwicky /UI News Bureau)

Highly sought-after

UI’s three-year residency program prepares veterinarians to care for zoo and aquatic animals

In partnership with the Chicago Zoological Society’s Brookfield Zoo and the John G. Shedd Aquarium, the UI College of Veterinary Medicine offers a three-year residency in zoological and aquatic animal medicine.

During their first year, residents work at the Veterinary College in Urbana, where they participate in caring for zoological companion animals (such as birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians and exotic mammals) that have been brought by their owners to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital. They also spend time in the College’s Wildlife Medical Clinic, which provides care to about 2,000 ill or injured wild animals brought in by the public each year. These patients range from raptors and waterfowl to foxes, cougars, turtles and snakes, and their care is supported entirely by donations.

Residents in their second and third years rotate between the Shedd Aquarium with its collection of fish, penguins, whales and dolphins, and Brookfield Zoo , home to more than 3,000 animals (and not a few who wander in from the wild). Although they are mentored by veterinarians at both Chicago-area facilities, Langan provides residents with weekly programmatic instruction. In addition, residents rotate through the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, Calif. Its aim is to protect and preserve marine ecosystems.

It’s this variety of experience that has made the UI program a top choice for DVM graduates. “Quite simply,” says Dr. Peter Constable, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine, “it is probably the most sought-after zoo residency in the country.”

Not only do the numbers bear him out—last year, the school accepted only one out of 80 applicants—but so does the success of its graduates. Many have landed top jobs at aquaria and zoos across the U.S., including zoos in Denver, Los Angeles, Miami, San Diego and Columbus, Ohio, as well as at the aquaria in Atlanta and Mystic, Conn.—J.B.