Cancelled

(Image courtesy of Paul Thompson/FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

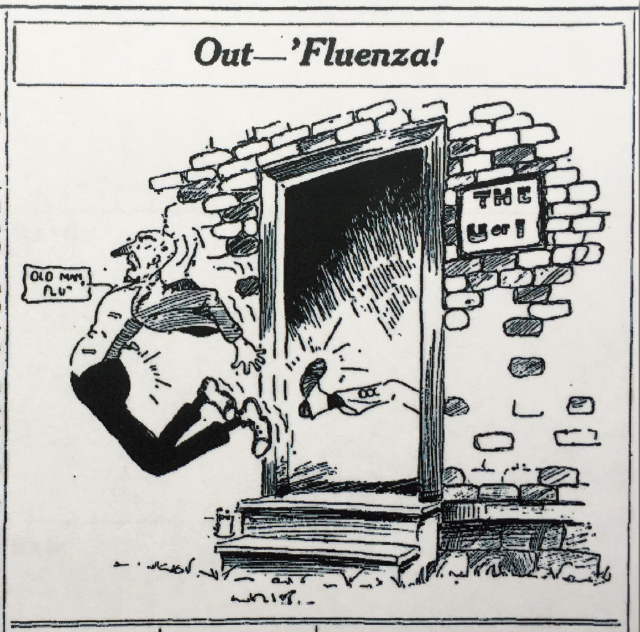

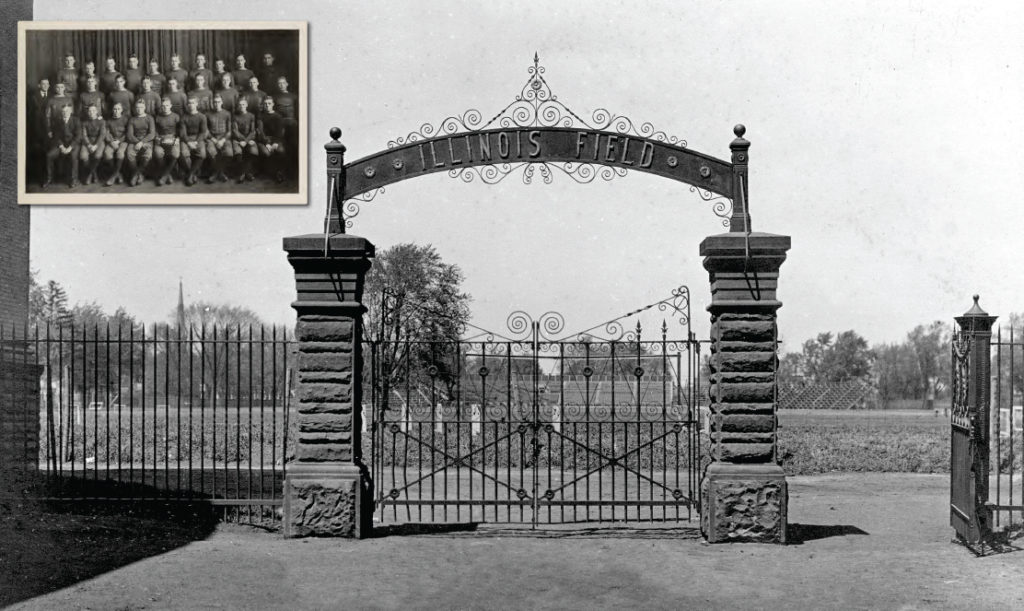

(Image courtesy of Paul Thompson/FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Under a gray and drizzling October sky in 1918, freshman Fred H. Turner stood at the locked iron gates of Illinois Field, then located north of the Engineering Quad. He watched from afar as his home team played a squad of Navy men stationed at Chicago’s Municipal Pier. The stands were vacant and the football field unusually quiet except for a small contingent of deans, administrators and military officers who cheered the players on. The Daily Illini wrote that the game “was one which was too good to throw away on empty stands, but the few military men who were there made up for the deficit in spectators by cheering their hardest.”

1918 was a year like no other. World War I raged overseas. The four-year armed conflict had left cities and villages abroad in ruins and 15 million people dead, including thousands of American soldiers buried in French fields far from home.

Another war simultaneously raged around the world that year, one with an enemy invisible to the eye and seemingly impossible to stop—influenza. It exploded into the deadliest pandemic the world had seen since the bubonic plague wiped out nearly half of the world’s population in the 14th century. But while that disease killed 75 million people over 100 years, it took the influenza pandemic only 15 months to kill 50 million.

The 1918 flu moved so quickly, many communities simply shut down. Dances were cancelled, movie theaters closed, public interaction discouraged—all in hopes of slowing the flu’s rampage.

Turner himself was recovering from the virus and knew firsthand how debilitating it could be. By the time he stood at the stadium gates, 1 million Illinois residents had been infected, and hundreds of his fellow students and army recruits lay ailing in campus buildings converted to emergency makeshift hospitals.

As he watched the empty bleachers collect rain while the world around him was consumed by war and illness, Turner was witness to a small piece of Illinois history set in a much larger historical moment.

At the University of Illinois, 1918 was the year without Homecoming.

A young tradition pauses

Homecoming was a relatively new concept in 1918, not only at Illinois but across the nation. While former students often returned to their college campuses for spring graduation, two Illini—Clarence Foss Williams, 1910, and W. Elmer Ekblaw, 1910—argued that commencement didn’t encourage enough fellowship between alumni and students. By graduation day, they noted, most students had already left campus for summer break, and seniors were too preoccupied with the ceremony.

Williams and Ekblaw suggested to campus leadership that alumni return to campus for an event-filled weekend during the fall instead. After much discussion and planning, the first Illinois Homecoming was held in 1910 and drew thousands back to UI. Banquets were served, class reunions held, and orange and blue bunting hung from the University buildings.

The peak of the inaugural festivities came on Saturday afternoon at Illinois Field, where alumni and students watched the Fighting Illini battle the rival University of Chicago Maroons. That first Homecoming was a rousing success, and the tradition remains one of the most beloved events on campus more than 100 years later. “There has only been one year when Illinois did not celebrate homecoming and that was in the fall of 1918. Once the danger of (what was then called) Spanish Influenza became clear, all plans for celebration were set aside.”

The pandemic takes hold

The influenza pandemic swept across the world in three waves. The first occurred in the spring of 1918, facilitated by World War I troop movements. The number who fell sick was notable, but the illness was mild and didn’t raise alarms.

The next influenza wave struck that fall, this time with greater virulence. The conditions of war—including close quarters and poor sanitation—escalated the spread of the flu, not only in the trenches and training camps, but also on transport ships crossing the Atlantic. By the time the SS Leviathan docked in New York City in early October 1918, it carried more than 2,000 cases of influenza among the 9,000 troops returning from France. Future U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, was one of its victims, developing pneumonia onboard. Like many others, he landed so weakened, that he had to be carried off of the ship.

The second influenza wave was markedly different from the first: Many more people were infected; mortality rates were higher; and, unlike the previous strain, it targeted young adults.

The first reported case of influenza at Illinois was diagnosed on Sept. 27, 1918, and the speed with which the virus overtook campus mirrored its spread worldwide. People quickly realized that this flu variant passed from one person to another at an exponential rate, and was deadlier than any influenza that had preceded it.

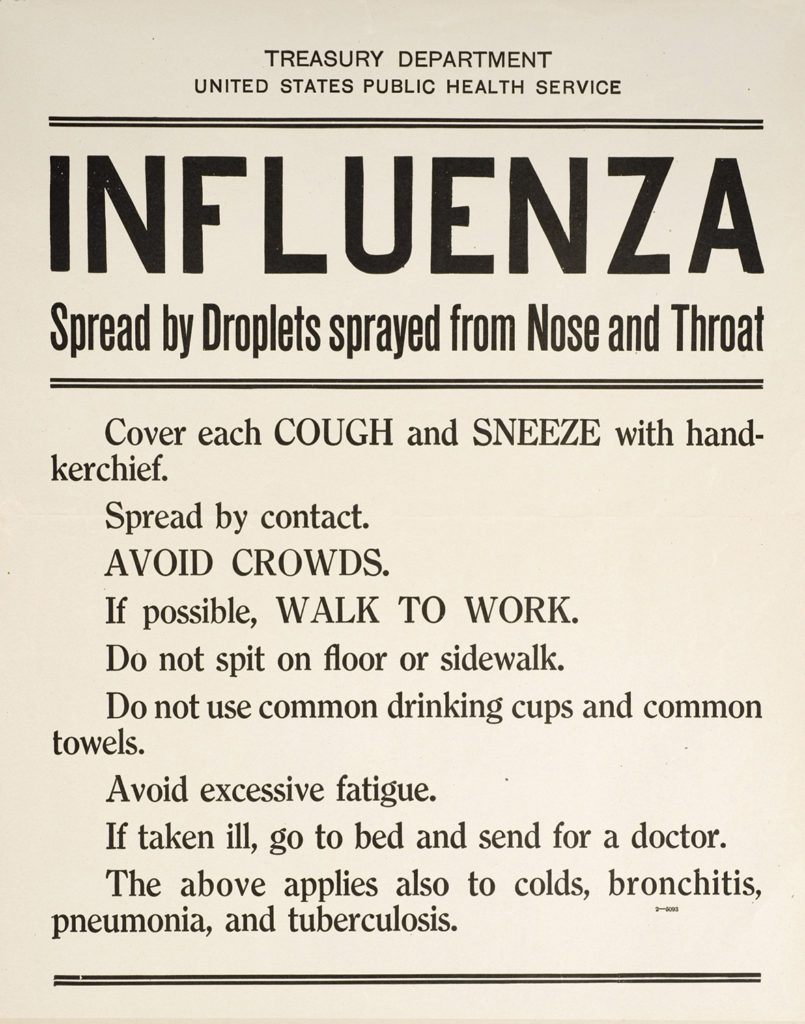

The U.S. Public Health Service encouraged Americans to take multiple precautions. Its posters and newspaper advertisements advised people to avoid crowds and public transportation, to cover coughs and sneezes, and to stay home if they were sick—some of the same preventive measures recommended today. Fresh air and open spaces also were advocated, from keeping bedroom windows open to walking to work. In San Francisco, for example, some judges even held court outside.

As government and public health officials began to uniformly discourage public gatherings, the University campus followed suit. By Oct. 6, sorority rush season was postponed indefinitely. Organ recitals were cancelled. And members of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) were ordered to avoid “groups around soda fountains, pool halls and cigar stores, and to stay away from moving picture shows and dances.”

But despite these measures, students still became sick—far too many for the small University hospital to handle. Campus staff transformed fraternity houses and dance halls into makeshift infirmaries, stood by bedsides as student fevers raged, and answered daily telegrams and letters from worried parents.

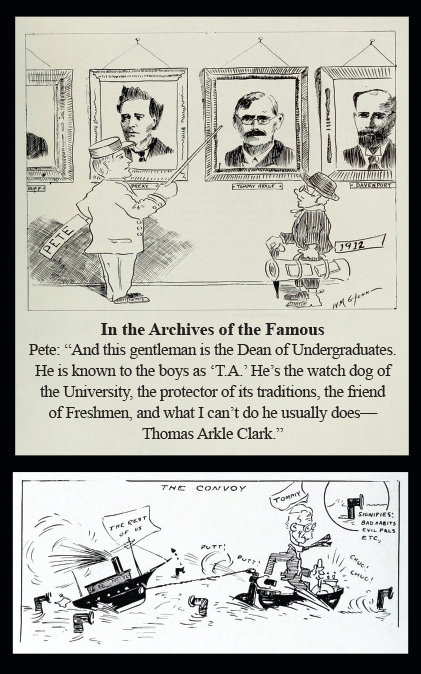

During this tumultuous time, one man emerged as a much-needed campus leader: the University’s Dean of Men, Thomas Arkle Clark, simultaneously a counselor, enforcer, friend and father figure to thousands of students.

Known for his high energy and chock-full schedule, Clark saw hundreds of students a day. One of his close friends described him this way: “Nobody goes to more dances and dinners, as well as funerals and faculty meets, than he. He will manage to get around to a smoker, a meeting of church deacons, an operation on an undergraduate in the hospital, a dance and a theatrical rehearsal in an evening, and be dictating letters at eight the next morning.”

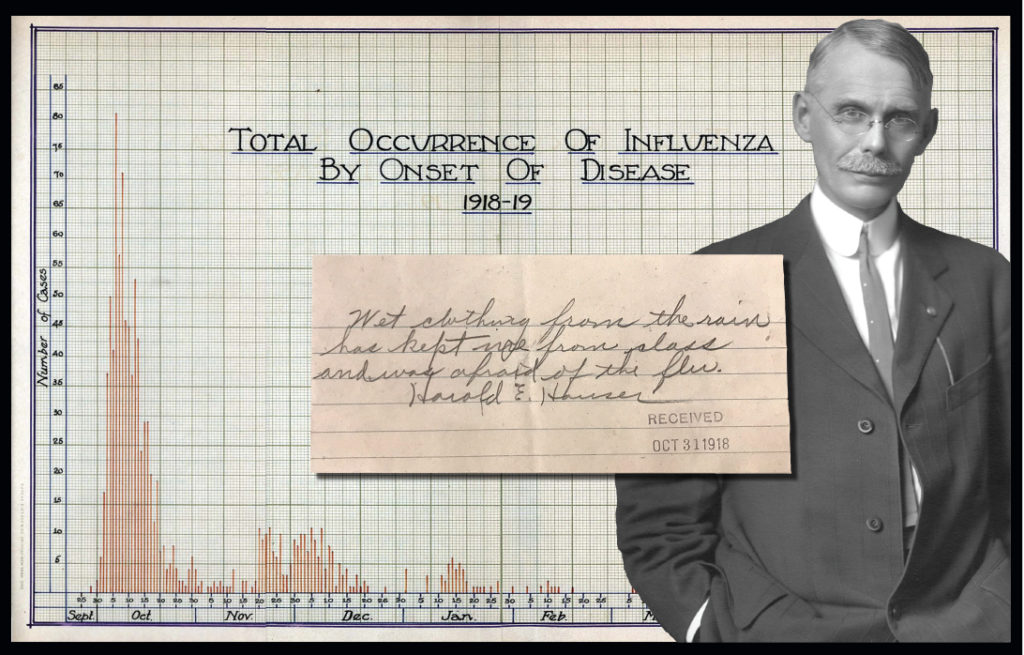

Cases of influenza at Illinois spiked during October 1918, mirroring reports worldwide. Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark (Right) played a key role in keeping UI from being overwhelmed by the virus. (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

War comes to campus

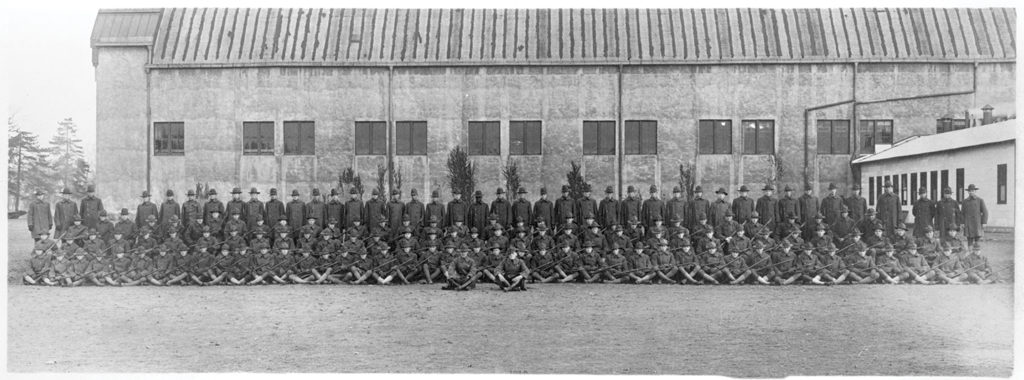

During the summer of 1918, the War Department established the SATC in an effort to attract more recruits. Men who enlisted in the SATC became privates in the U.S. Army and attended college. Placed on active status, they could be deployed at any time. The government paid for their tuition and housing, and gave each recruit a monthly stipend of $30 ($539 in today’s dollars).

The program attracted 140,000 men on 525 university campuses across the nation by the fall semester. Illinois welcomed nearly 3,500 student soldiers, who represented almost half of the student population.

Clark spearheaded efforts to transform fraternity and sorority houses, as well as private homes used as campus rentals, into military housing. The drill floor of the newly constructed Armory housed 1,500 men who slept on row upon row of beds under the building’s 98-foot-high dome. Some cal

led it the “biggest bedroom in the state.”

During the summer of 1918, the U.S. Dept. of War established the Student Army Training Corps to attract more recruits. At Illinois, 1,500 soldiers were housed on the drill floor of the newly constructed Armory building. (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

SATC members were inducted on Oct. 1, University classes began on Oct. 3, and by Oct. 4—only one week after the first on-campus flu case was reported—the number of influenza cases began to swell. Data gathered worldwide showed an almost implausible spike in the number of flu victims, and at Illinois, the numbers of the sick grew daily.

“I am in a whirlwind of work running or trying to run this whole machinery of the SATC,” Clark wrote to a close friend and colleague. “We have more than 100 people in the hospital and no nurses. I am drafting or attempting to draft the University women [as nurses].”

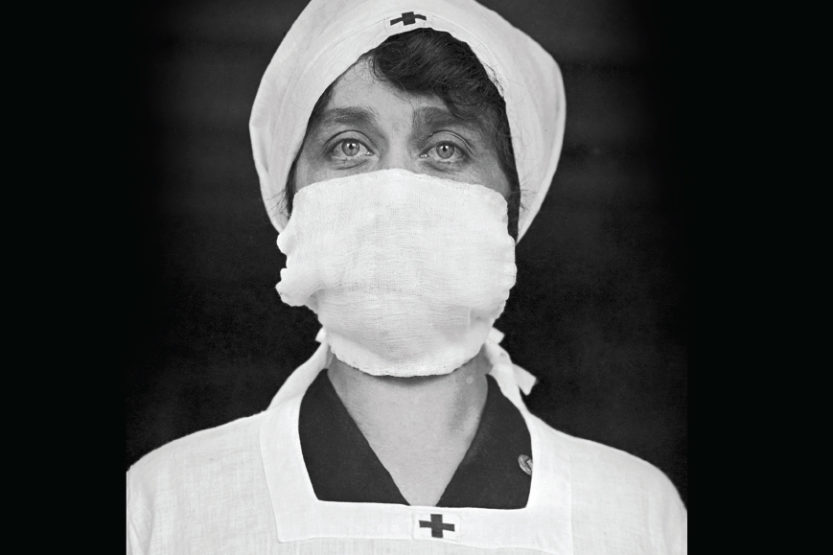

The Nov. 1, 1918 issue of the Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly News confirmed that “The demands for medical attention [have] entirely exhausted the efforts of local doctors, and nurses [are] simply not to be had. Miss Olive Condit, the nurse in charge, [has] stuck to her post throughout the epidemic.”

The upheaval created by coordinating the SATC now overlapped with the pandemic. With no time to rest, Clark moved from one massive undertaking to another.

It is easy to imagine the dean hurriedly crossing campus to check on students in the many emergency hospitals, his signature

making him instantly recognizable. Clark was steadfast and calm under pressure, but as the weeks passed, his letters to friends illustrated the enormity of the situation.

“We certainly are making things hum here,” Clark wrote on Oct. 14, 1918. “How we have got done what we have, I cannot see. Two weeks ago tomorrow, we had room for seventeen in our hospital. We have more than 300 now and [have to] enlarge [bed capacity] every day and [obtain additional] supplies and nurses … my brain reels. We have lost two men so far. I have never had so big a job, and I have never been so proud of doing it.”

But in reality, Clark’s work was just beginning.

Concerns about the flu led to the 1918 Homecoming activities being cancelled. Only a small group of deans, administrators and military officers were on hand at Illinois Field to watch the Fighting Illini football team battle a Navy team stationed at Municipal Pier in Chicago. (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

Homecoming cancelled

By the end of October, by which time alumni were scheduled to flood campus in their Orange and Blue, while sophomores should have been trying to best freshmen in the annual class competition, Clark and his dedicated staff focused instead on keeping the campus from being overwhelmed by illness. In this effort, Clark was joined by J. Howard Beard, M.D., head of the University’s Health Services Station, and Athletics Director George Huff, all three of whom are remembered for their unfailing devotion in seeing the campus through its darkest times.

Fear was spreading along with the disease, and some students were afraid to go to class. At one point, the alumni newsletter reported that Clark, along with Beard, “helped to carry breakfast to the patients in College Hall when the servants became panicky and refused to go in.”

On Oct. 22, Clark wrote: “I don’t feel like the same person, and I haven’t for the last two months. I seem [to be] somebody else, working in a new world and under new conditions. We have had 1,000 people sick with influenza and nine deaths. There will be others I am afraid, too. This is a horrible disease.”

This was the state of affairs as Homecoming Weekend 1918 approached. Despite the cancellation of all other alumni events, the Fighting Illini showed up for the Homecoming football game at Illinois Field on Saturday, Oct. 26, to take on a Chicago-based Navy team.

By the beginning of November, it seemed the worst was over, but the pandemic kept hospitals busy through the end of the year. A third flu wave in the spring of 1919 was much like the first.

Over the course of those harrowing months, 2,500 Illinois students were treated in University hospitals—roughly 37 percent of the school’s 6,600 students. In all, 19 students died. The attentiveness with which doctors, nurses and University officials cared for and protected Illinois students prevented many more deaths than might have been expected. Compared with other state universities, Illinois had one of the lowest mortality rates of the pandemic.

Campus heroes for extraordinary times

Clark, Beard, Huff and others were all recognized for their remarkable efforts under these unprecedented and difficult conditions. They, along with campus doctors and nurses, put themselves at risk in order to selflessly care for the very ill.

When Huff passed away in 1936, Beard credited him for saving many students’ lives during the influenza crisis. “He worked feverishly and lost a lot of sleep in those days, and many were the times we said goodnight at midnight,” Beard said.

Upon his own passing in 1950, Beard was similarly remembered by none other than Turner. After his tumultuous first semester on campus, Turner worked for Clark throughout his undergraduate years, became his trusted confidante, and ultimately succeeded Clark as the Dean of Men in 1931.

Turner released a written memorial for Beard co-authored with other University officials: “He was a man of rare character and personality … conscientious, sincere and kindly,” the memorial stated. “All of his deeds were characterized by his unfailing ability and integrity, and he refused to deviate from the highest principles of his profession.”

As for Clark, over the course of his 38-year career at Illinois, he became a legendary figure. He was both beloved and feared—no one wanted to receive a summons from him because they knew it meant they were in trouble. He knew nearly everyone’s name, and it was rumored he had a spy network on campus that brought him reports of misdeeds. He was so much like a parent, the students even created a jingle describing him:

“A father to the girls, a mother to the boys … Our matriarchal, patriarchal Thomas Arkle Clark.”

Clark passed away on July 18, 1932. As the nation’s first dean of men, he set the standard for the role as it emerged at other universities. Upon his death, Harry Woodburn Chase, then University president, praised Clark’s “keen knowledge of human nature, his passionate desire for moral up-building of youth and his literally tireless devotion to his work.”

Clark’s obituary in The Daily Illini may have best summed up his importance to the University’s students: “What would have happened to the undergraduates at Illinois had not some such man arisen to better their conditions, assure them justice and sympathy, and to give now and then a bit of fatherly advice, is difficult to imagine.”

The UI campus recovered from the 1918 flu pandemic due to the selfless efforts of many faculty, administrators and healthcare professionals who joined forces to face an extraordinary crisis. A century later, few students know the stories behind the campus building names that commemorate the leaders of those efforts. Huff and Clark are memorialized with Huff and Clark Halls, which anchor the corners of Fourth and Gregory Streets. Turner is honored with the Turner Student Services Building. Their legacy is etched not only in the buildings’ stone, but also in the enduring, steadfast character of the University of Illinois.

As Clark wrote, “Nobody was neglected here, but that was because we took care of them.”

Excerpted from “1918: The Year Without a Homecoming.” To read more, visit storied.illinois.edu/flu.