Memory Lane: Lost Cities of Elms

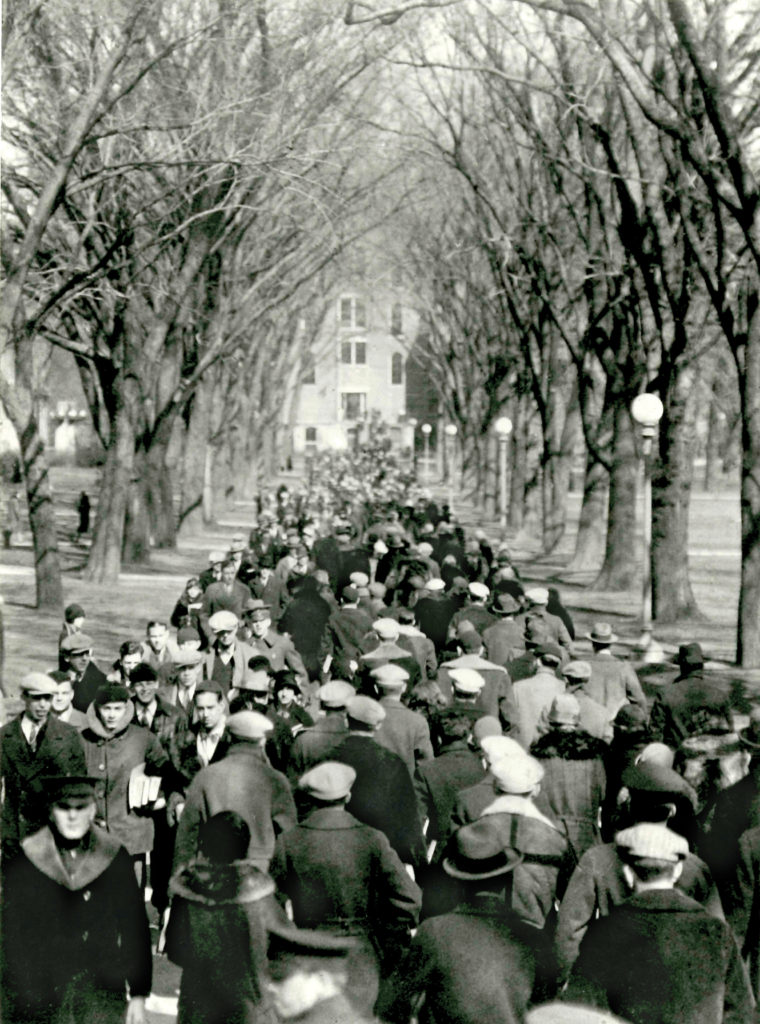

Before Dutch elm disease and phloem necrosis devastated their population, American elms lined the walkways of the Quad and could be found throughout the campus. Numbering 1,850, they represented 90 percent of all trees at Illinois. (Image courtesy of UIAA)

Before Dutch elm disease and phloem necrosis devastated their population, American elms lined the walkways of the Quad and could be found throughout the campus. Numbering 1,850, they represented 90 percent of all trees at Illinois. (Image courtesy of UIAA) It stands on Race Street, on the very edge of campus—a survivor from a more genteel time when stately American elms formed lush, green archways over many small-town and suburban streets, their graceful branches swaying and creaking in the light breeze of a sultry summer afternoon. Somehow, this majestic American elm on Race Street has endured a double onslaught of disease that ravaged the U.S. elm population, beginning in 1930. The University of Illinois was especially hard hit—a whopping 90 percent of campus trees were American elms. The elm catastrophe of the 1950s may be the single most devastating blow ever dealt to the beauty of the UI campus.

A campus without trees was unthinkable. Experts such as horticulturist J. C. Blair and botanist C.F. Hottes credited trees with making the UI campus one of the nation’s most beautiful. “Without them [the trees] to relieve the stern hues of the brick buildings and the monotonous level of the greensward, the campus would be as dull and uninteresting as the prairie,” an observer remarked in 1908.

Disaster first struck UI elms in 1949 when two trees on the south campus were discovered to have phloem necrosis—an invariably fatal viral disease. Two years later, in a fearful one-two punch, Dutch elm disease invaded the campus, arriving, it was believed, via a beetle that had hitchhiked on an Illini football fan’s car. First introduced to the U.S. in 1930 from Europe, this fungal disease is spread by elm bark beetles.

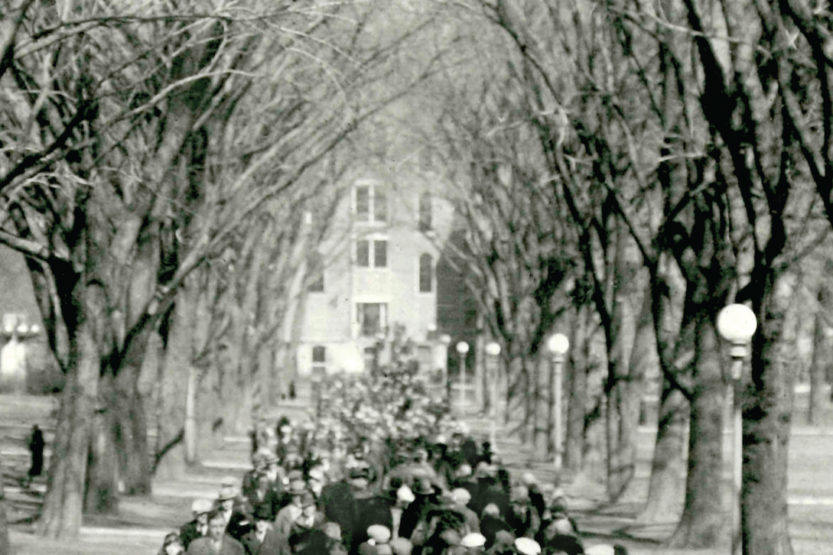

University officials vigorously responded to the emergency with spray trucks and tree-cutting crews, but it was all for naught. In a little over a decade, only 92 of the 1,850 campus elms remained, while all of the elms located on the Quad were wiped out.

Afterwards, the Quad resembled a blast zone. In 1956, thornless honeylocust trees were planted to replace the towering elms that once shaded generations of students promenading on the Boardwalk. But the Daily Illini deemed them “no match for the elms.”

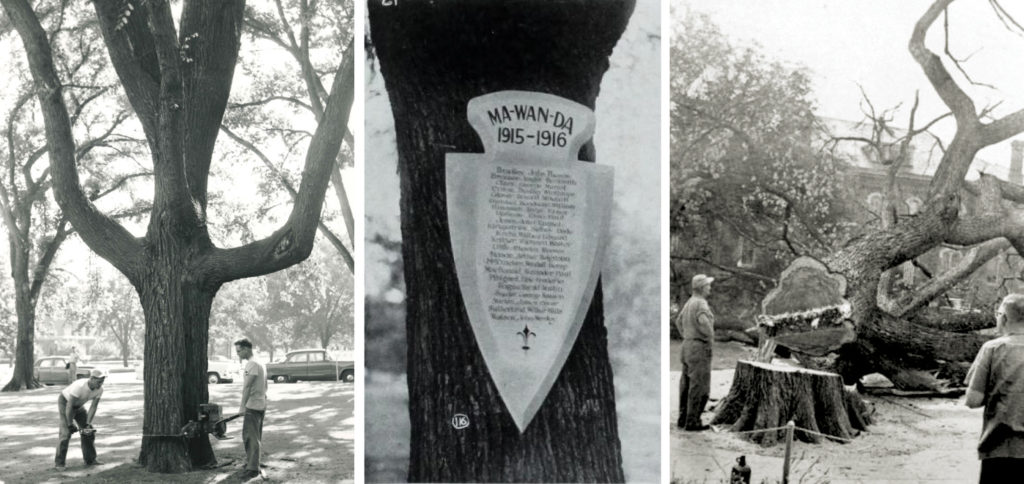

Phloem necrosis first appeared in 1949 and Dutch elm disease followed two years later. In a little more than a decade, the elm tree population had been reduced to 92. The most heartbreaking loss was the death of the 83-year-old Ma-Wan-Da elm in front of the Illini Union. (Images courtesy of Illios 1917 and 1959.)

The death of the Ma-Wan-Da elm in front of the Union especially tugged at Illini heartstrings. For decades, the Ma-Wan-Da senior men’s activity and honors society had hung arrow-shaped plaques on the landmark tree bearing the names of new members. The University took special pains to save it, but alas, the Ma-Wan-Da elm succumbed to phloem necrosis in 1958. With only three cuts of a Physical Plant power saw, the 80-foot-high, 83-year-old tree came tumbling down.

“I have always insisted that there would be a few [elms] that would survive, but I’m beginning to get a little pessimistic about that now,” J.C. Gabbard, a physical plant staffer, remarked in 1961.

The American elms on campus continued to die—one had to be removed as recently as 2008—but a few have survived like the one on Race Street.

“It is lovely in itself,” arborist Jean Burridge wrote of the solitary Race Street elm, “but one cannot but look for the lost cities of the elms.”