Saving Pretzel

In the spring of 2016, Pretzel, a red-standard dachshund, was diagnosed with glioma, a tumor that grows in the brain and nervous system. Her treatment program included chemotherapy and daily doses of the drug PAC-1, which triggers an enzyme that causes cancer cells to self-destruct. At the trial’s conclusion in August 2016, Pretzel’s tumor had shrunk by 43 percent. (Image Courtesy of Donna Gescheidler)

In the spring of 2016, Pretzel, a red-standard dachshund, was diagnosed with glioma, a tumor that grows in the brain and nervous system. Her treatment program included chemotherapy and daily doses of the drug PAC-1, which triggers an enzyme that causes cancer cells to self-destruct. At the trial’s conclusion in August 2016, Pretzel’s tumor had shrunk by 43 percent. (Image Courtesy of Donna Gescheidler) On the day we meet Pretzel, the weather is chilly and clear in Hammond, Ind., where she lives with her owners, Donna and Dave Gescheidler. Their living room décor anticipates Christmas, less than two weeks away, lively with greenery and patient little buildings and dancing figurines. But the best present of the season has already arrived. A visit to the clinic yesterday affirmed that the health of the little dachshund, a purebred red standard, continues stable—despite the tumor in her brain.

“When she was diagnosed, she was given six months,” says Donna, a self-employed accountant, devoted grandmother and lifelong lover of dogs. This love extends most emphatically to Pretzel, who, at the age of 9, is entering her third year as a cancer survivor, thanks to a clinical trial by two UI professors.

The dog lies calmly next to her mistress on their living room sofa, brown eyes liquid-dark, gaze distant but warm. Pretzel is always calm—“she’s a senior,” smiles Donna—save when visitors come to the door or other dogs are so bold as to enter the premises.

A retired breeding dog, Pretzel had a seizure in the spring of 2016, almost a year after the Gescheidlers adopted her at the age of 6. Then came a second seizure. A trip to the family vet led to an MRI and a very scary diagnosis by Michael Podel, a veterinary neurologist in Chicago. Pretzel had glioma.

Glioma is insidious, even for a cancer. A tumor, the disease spreads relentlessly into neighboring healthy brain tissue, causing havoc. Chemotherapy and radiation are standard treatment for dogs, as for humans, in whom the cancer is known as glioblastoma—the disease afflicting U.S. Sen. John McCain and the disease that took the life of former vice president Joe Biden’s son, Beau. While conventional treatment shrinks the cancer, glioma/glioblastoma is notorious for reoccurrence. Neither dogs nor people diagnosed with the disease get assigned very lengthy timelines.

After she got the news about Pretzel, Donna says, “I cried all night.” But she also was thinking about something that Podel had told her. Pretzel was eligible for a clinical trial of an anticancer drug called PAC-1. By mid-April, Pretzel was enrolled. By mid-August, when the trial concluded, the dog’s tumor had shrunk by 43 percent.

UI veterinary oncologist Dr. Timothy Fan (left) and UI chemistry professor Paul Hergenrother developed a PAC-1 clinical trial using companion animals diagnosed with cancer. For owners of critically ill dogs and cats, a clinical trial means access to cutting-edge care. For researchers, the results are much closer to those from human trials than those from laboratory studies of rodents. “Companion animals are exposed to many of the toxins that we are,” Hergenrother says. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer)

Slipping past the blood-brain barrier

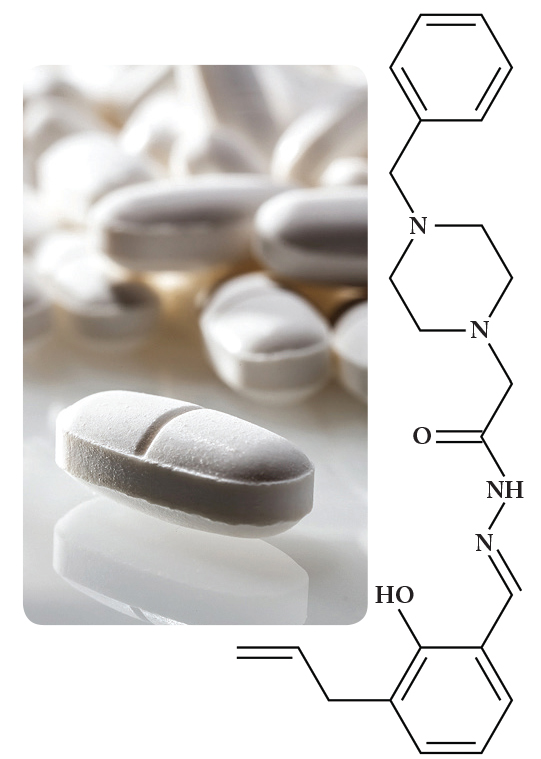

UI chemistry professor Paul Hergenrother works in Roger Adams Laboratory, a vintage campus building near the Quad, with its front on Mathews Avenue and a big stack of labs appended in an annex on the back. His research is devoted to chemical compounds that attack drug-resistant bacteria, cancer cells and other diseases. A decade ago, Hergenrother discovered the drug PAC-1, which triggers a deadly enzyme that causes cancer cells to self-destruct. PAC-1 shows promise as a treatment for lymphoma and osteosarcoma and even more hope for treating the brain cancers of meningioma and glioma/glioblastoma.

Remarkably, the drug can cross the blood-brain barrier, a membrane of capillaries that, in both humans and dogs, protects the brain by rebuffing pathogens and toxins—and, less fortunately, blocks most anticancer drugs.

“There are certain molecular features that are correlated with the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, but transport through the blood-brain barrier is not fully understood,” says Hergenrother, whose lab has screened some 20,000 potential anticancer compounds using high-throughput technology. “We have tried to advance those that are blood-brain- barrier-penetrant to treat brain cancers,” he observes. “It was not explicitly part of the [drug] design process. But it is something that we recognized early on and wanted to take advantage of.”

Since 2006, when Hergenrother discovered PAC-1, research on the drug has included testing in human cell lines and in rodents, and in 2015 a clinical trial of PAC-1 for late-stage cancer patients began. (A second human trial was recently launched—see sidebar below.) Not long after work had begun, Hergenrother received a call from Tim Fan, PHD ’07 VM, a UI professor who runs the Comparative Oncology Research Laboratory at the College of Vet Med’s Small Animal Clinic. Fan had read about Hergenrother’s work on PAC-1 and he had a proposal. How about a PAC-1 clinical trial using companion animals diagnosed with cancer?

THE HUMAN EQUATION: In November 2017, a new human clinical trial of the cutting-edge anticancer drug PAC-1 was launched. Open to patients with advanced brain cancer (glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma), the trial offers treatment of PAC-1 in combination with the chemotherapy drug temozolomide. The therapy is similar to that received by Pretzel and two other dogs in a promising 2016 clinical trial of pets with cancer. (See main story.) The trial is sponsored by Vanquish Oncology, a startup founded by Paul Hergenrother, the UI chemistry professor who discovered PAC-1, with support from an angel investor. For more information, visit the PAC-1 trial page on the National Institutes of Health website: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03332355. —M.T. (Images courtesy of Paul Hergenrother)

Veterinary medicine is rich with connections to human medicine—both disciplines seek to determine what causes diseases, the ways in which they spread, and how to develop effective treatments. In this interdisciplinary environment, the win-win of clinical trials with pets has emerged as a compelling model. For owners of critically ill dogs and cats, a clinical trial means access to cutting-edge care. For researchers, the results are much closer to those from human trials than those from laboratory studies of rodents, where “you’re giving the mouse cancer and then you’re curing that mouse,” as Hergenrother explains. “The cancer is not naturally occurring.” Indeed, the paradigm is even broader. “Companion animals are exposed to many of the toxins that we are and, in many cases, come down with similar cancers,” he adds.

The first clinical trial of PAC-1 in pets began in 2007, and the two UI professors have been working together ever since. Hergenrother creates the compounds for testing while Fan organizes the trials, which draw on the expertise and practices of veterinary clinicians, such as Jayme Looper, Pretzel’s radiation oncologist, and Podel, the neurologist who diagnosed the dachshund and offered Donna life-changing access to PAC-1.

Collaborations extend to researchers and clinicians at institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Ohio State, University of Wisconsin—Madison, University of Pennsylvania, Virginia Tech and the National Cancer Institute. On the Illinois campus, the Carl Woese Institute for Genomic Biology has introduced “Anticancer Discovery: From Pets to People” as an interdisciplinary research theme. Both Hergenrother and Fan have labs in the prestigious facility and share data and ideas with other UI faculty in fields such as biochemistry and computational biology.

For Fan, the synthesis of veterinary oncology and state-of-the-art cancer research highlights the strength and resilience of the University. “It’s a very homegrown program,” he says. “The PAC-1 story spans a decade of Paul generating it in his lab and then testing it here in dogs and in human clinical trials. I don’t think there is, to my knowledge, any other veterinary institute that has served in that capacity.”

A survivor—and a star

Pretzel began her 84-day course of treatment in April 2016, receiving daily doses of PAC-1 administered by Donna, along with a chemotherapy drug. The PAC-1 tablets the dog received are identical to those administered in human clinical trials.

For more than three weeks, Dave drove Pretzel every weekday to the MedVet Medical & Cancer Center for Pets in downtown Chicago for 7:30 a.m. radiation treatments administered by Looper.

“Everything had to be on a certain date at a certain time,” Donna recalls. “It was a lot of trips into the city.” Side effects were few—another apparent benefit of PAC-1. Even chemotherapy and radiation didn’t seem to bother the stoic, sweet-tempered dog that much, except for a bit of fatigue and some loss of appetite. By the time the trial concluded in August 2016, Pretzel’s tumor had shrunk by 43 percent. The two other dogs in the trial showed even better results. Breta, a boxer, had a tumor that shrunk by 60 percent. Piper, the third dog in the trial, had a tumor that was vanquished by 100 percent (though Piper, alas, succumbed to other causes).

If Pretzel’s clinical trial was unusual, certain aspects of her survival can only be termed spectacular. In October, she was invited to the stage of the State Farm Center on campus for the kickoff of “With Illinois,” a major UI fundraising campaign. As part of the 90-minute celebration of achievements and breakthroughs at Illinois, Hergenrother and Fan shared the story of their anticancer research with the audience. Then Donna walked Pretzel onstage, the little dog’s ears bedecked by orange ribbons and an Illini collar around her neck, hung with a medal of St. Francis for good measure. The crowd went crazy. Pretzel was a star.

As she and Dave packed up to return to Hammond, “people were yelling, ‘Goodbye, Pretzel!’” Donna recalls, with obvious joy. But she remains realistic. “I was told from the beginning that brain tumors go away but come back,” she tells us on the day we meet Pretzel. “The objective of the treatment is to shrink the tumor and slow its growth.” The same uncertainties, of course, face humans who have brain cancer.

“I just feel in my heart,” Donna says as she strokes Pretzel’s silky brown fur, “that I’m going to have her for a long time.”