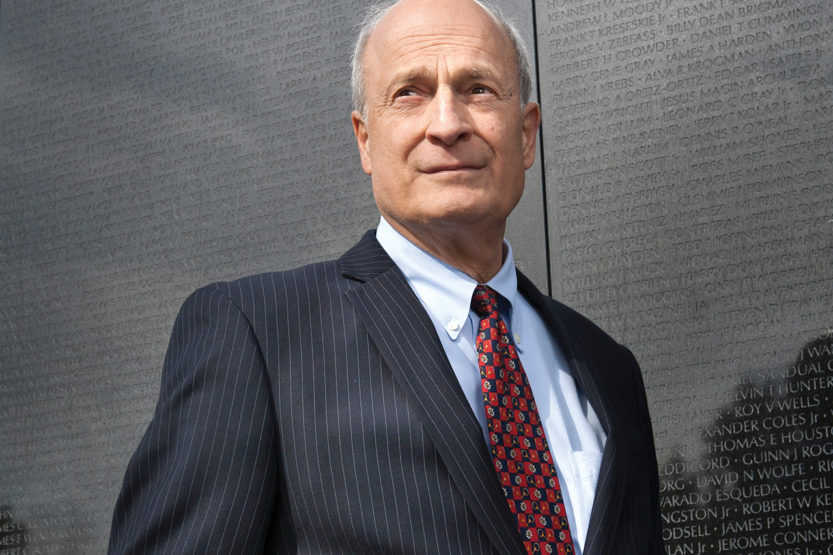

Alumni Interview: Robert Doubek

“For many people, the memorial has such significance—they are almost at the grave of their loved ones,” says Robert Doubek, ’66 LAS, who co-founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, and oversaw the memorial’s design and construction. (Image by Katherine Lambert)

“For many people, the memorial has such significance—they are almost at the grave of their loved ones,” says Robert Doubek, ’66 LAS, who co-founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, and oversaw the memorial’s design and construction. (Image by Katherine Lambert) The Washington Post’s architecture critic called the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund “a clipper ship of efficiency.” Part of it was the fact that we were all young. The effort was founded by former junior officers and enlisted men. When the project started in 1979, I was 35. When it ended in ’82, I was 38. And others were younger. The idea was that it wasn’t going to be an ongoing effort. It was a one-time project. It was just a matter of moving forward as quickly as possible with every activity. Jan Scruggs, John Wheeler and I were considered a troika of leadership.

Once we got an Act of Congress signed on July 1, 1980, it was a big feather in our cap. Until that time, the fund was just another nonprofit. Now, we had Congress authorizing us to use two acres of the most valuable real estate in the country—in Constitution Garden, between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. From the beginning, everybody kept asking, “Well, what’s it going to look like?” On May 7, 1981, we held a press conference to announce the design, which really made the memorial front-page news.

It was our philosophy that the rancor over the war had deprived Vietnam veterans of recognition for their service. So, from the beginning, we had four major criteria for the design in the competition. The first criterion was that the memorial itself could not make a political statement about the war—it could not say the war was right or wrong. Second was to honor all who served—that the names of all who died or were missing in action would be inscribed as a special tribute. Third, the memorial would be harmonious with its surroundings. And fourth, it would be reflective and contemplative in character. The design that was chosen appeared to meet those criteria exactly. But it turned out that some people did not share our vision of helping to achieve national reconciliation.

There’s something about the power of a name. For many people, the memorial has such significance—they are almost at the grave of their loved ones.

There was a strong overlap between people who hated the design and, you might say, very conservative people. There was columnist Pat Buchanan. James Webb [then a staff member of the House Committee on Veteran Affairs] was a leader in the fight against it. The Secretary of the Interior, James Watt, was poised, at one point, to shoot the whole thing down, but the White House convinced him to hold off, mainly because major veterans organizations were on our side. The American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars totally supported us in getting the memorial built.

I was in charge of operations. I coordinated passage of the Act of Congress. It was my idea to do direct-mail fundraising, which I initiated using a professional PR firm. I managed the design competition and obtained all the federal government approvals for the design—there were 13 formal hearings. With Maya Lin [the Yale architecture student whose design won the competition], I selected the architect of record and the construction company. And I organized and directed the dedication ceremony, attended by 150,000 people.

I know every detail of the memorial. I know every crack. I know where names have been reinscribed to correct misspellings. When I look at the memorial from a purely artistic point of view, I see a magnificent, gleaming, polished black object in a beautiful garden of green grass. When I walk down low enough that the walls are above my head, especially in the morning or the late afternoon, I find myself almost in a magical place. On one side, you have the green lawn, sky and trees. On the other side, you have these translucent names imposed upon your view. There’s something about the power of a name. For many people, the memorial has such significance—they are almost at the grave of their loved ones.

Go there any summer day or weekend, and you’ll see lots of visitors. The memorial is now an American cultural icon.

The job changed my life forever. I met my wife while working on it. I also met Virginia U.S. Senator John Warner, who helped us raise approximately $15,000 to get started, and actress Elizabeth Taylor [then Warner’s wife]; I have some anecdotes about Taylor in my book [Creating the Vietnam Veterans Memorial: The Inside Story]. And people like Ross Perot and Bob Hope. It was a heady experience for a bohemian boy from Berwyn, Ill.