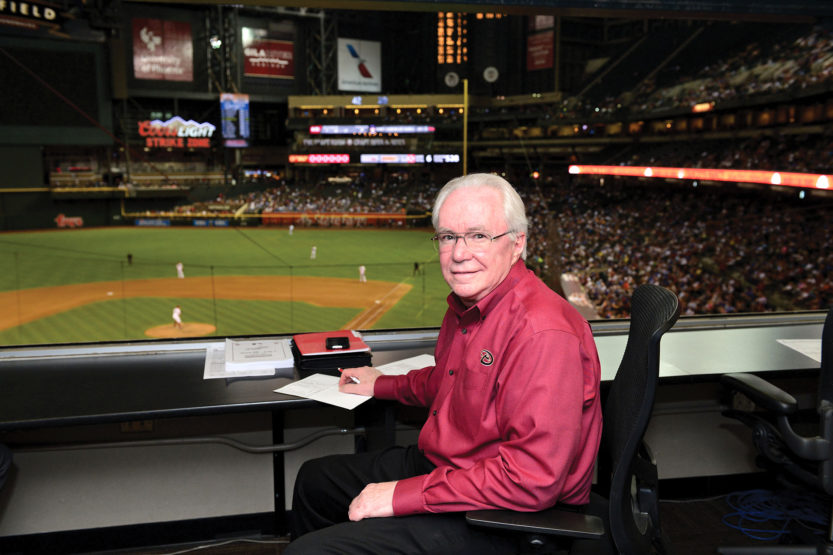

Meet stats man Ed Lewis

“I look for every insight I can glean…to create a winning edge,” says Ed Lewis, Arizona Diamondbacks director of baseball analytics and research.

“I look for every insight I can glean…to create a winning edge,” says Ed Lewis, Arizona Diamondbacks director of baseball analytics and research. Although Ed Lewis ’70 VM, DVM ’72 doesn’t swing a bat or shag fly balls, he plays a key role in his team’s success. As director of baseball analytics and research for the Arizona Diamondbacks—the first to hold that position for the team—Lewis mixes the science of statistics with the capriciousness of America’s national pastime to craft winning formulas for the team.

“The purpose of keeping statistics is to identify meaningful patterns,” Lewis explains from his book-lined office at Chase Field, the National League franchise’s home in Phoenix.

“We have the technology to measure every aspect of every pitch to the decimal point. We can track the vertical movement of the ball as it leaves the pitcher’s hand, the horizontal movement, the velocity of the pitch, the velocity of the ball coming off the bat, the trajectory of the hit ball. Mountains of data emerge from each game, and I look for every insight I can glean from those numbers to create a winning edge. You can bet the other team does, too.”

And most people assume baseball is simply a matter of tracking hits, runs and outs.

The wild card is the human element—the unpredictability of the batter who connects for a triple because the shortstop misjudged the ball as it hopped through the infield and struck a divot.

“There are aspects of the game you just can’t quantify,” Lewis acknowledges. “That’s the magic of baseball. What I track is the science.”

After each contest, Lewis breaks down the numbers and circulates reports among Diamondbacks coaches, who incorporate his findings into strategies for the next game.

Prior to a series, Lewis also creates a report on the opposing manager, providing Diamondbacks skipper Chip Hale with insight into how his counterpart may react in certain situations, so Hale can plan accordingly.

Scouting on that order of magnitude relies more on psychology than numbers, Lewis admits. “When you stu–dy people, you often notice ingrained patterns they’ve created for themselves,” he elaborates. “Former Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver kept little cards in his pocket to take notes on the strategies of other managers. He once said, ‘A good manager is always thinking what he’s thinking you’re thinking.’”

Lewis forged a circuitous path to the Major Leagues. Growing up on Chicago’s South Side, he was a die-hard fan of the American League’s White Sox, and played catcher and second base in Little League, dreaming of one day seeing his image on a baseball card. He combined a love of math, science and animal medicine in college and, after earning his DVM, opened a private veterinary practice.

All the while, baseball and numbers remained a part of his life. Lewis held season tickets to White Sox games and dabbled in the stock market, weathering numerous economic storms and eventually selling his practice in 1990.

Prior to that, in 1979, he met then-White Sox manager Tony La Russa, an animal lover who had founded an animal rescue foundation in California. The two became friends, and when La Russa was named manager of the National League’s St. Louis Cardinals in 1996, he inquired as to whether Lewis would like to scout the manager of the Houston Astros.

“As a former American League manager, Tony didn’t have much information on opposing National League managers,” Lewis recalls. La Russa later appointed Lewis to administrate Cardinals Care, the team’s charity organization. When La Russa became chief baseball officer for the Diamondbacks in 2014, he recruited Lewis to run the organization’s newly created analytics department. Having recently added two interns to assist him, Lewis says he was surprised by the caliber of candidates vying for the positions.

“I reviewed resumes from hundreds of applicants versed in analytics from schools such as Harvard, Yale and Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” he says. “One applicant held a Ph.D. in electrical engineering that could have earned him more than $200,000, but he applied for a minimum-wage job because of his love for baseball.”

But one game this numbers man won’t play is the lottery. “I’m a percentages guy,” Lewis says. “I’ve never bought a scratch-off ticket and never put a nickel in a slot machine. That’s not a good deal. There’s no bigger gamble than the stock market—that’s the world’s biggest poker game, and for 10 years, I was in the middle of it.”